Prev TOC Next

JB: So, let’s think about how we can prove this generalization of Gödel’s completeness theorem. First, remember that a hyperdoctrine B is consistent iff B(0) has at least two elements, or in other words, ⊤ ≠ ⊥ in this boolean algebra. Second, let’s say a hyperdoctrine C is set-based if every C(n) is the power set of Vn for some fixed set V. We call V the universe. Third, let’s say a morphism of hyperdoctrines, say F: B → C, is a natural transformation whose components F(n): B(n) → C(n) are Boolean algebra homomorphisms obeying the Beck–Chevalley condition and maybe the Frobenius condition. (We’re a bit fuzzy about this and we’ll probably have to sharpen it up.)

Then let’s try to prove this: a hyperdoctrine is consistent iff it has a morphism to some set-based hyperdoctrine.

Here’s my rough idea of one way to try to prove it: use Stone’s representation theorem for boolean algebras! This says any boolean algebra is isomorphic to the boolean algebra of clopen subsets of some Stone space. A Stone space is a topological space that’s profinite, i.e. a limit of finite spaces with their discrete topology. A subset of a topological space is clopen if it’s closed and open.

The clopen subsets of a topological space always form a boolean algebra under the usual intersection, union and complement. So, the cool part of Stone’s representation theorem is that every boolean algebra shows up this way—up to isomorphism, that is—from a very special class of topological spaces: the ones that are almost finite sets with their discrete topology. A good example of such a space is the Cantor set.

I hope you see how this might help us. We’re trying to show every consistent hyperdoctrine is set-based. (I think the converse is easy.) But Stone is telling us that every boolean algebra is a boolean algebra of some subsets of a set!

MW: Okay, that jibes with some of my own vague ideas. Though I hadn’t got as far as Stone’s Theorem. (I’m familiar with it, of course.)

Two ideas make Henkin’s proof work. One is to find a epimorphism of the boolean algebra B(0) to the two-element boolean algebra {⊤,⊥} (or equivalently, an ultrafilter on B(0)). In other words, we’re deciding which sentences we want to be true; this is then used to define the model. The points of the Stone space are these epimorphisms, so we’re further along on the same track.

The other idea—specific to Henkin—insures that quantifiers are respected. Syntax now comes to the fore: We add a bunch of constants, called witnesses, and witnessing axioms, like so (in a simple case):

∃x φ(x)→φ(cφ)

where cφ witnesses the truth of the existential sentence ∃x φ(x).

Stone’s Theorem gives us a Stone space Sn for each B(n). That’s nice. But we don’t immediately have Sn=Vn, with the same V for all n. (I’m not even sure that we want exactly that.)

The Henkin witnessing trick “ties together” (somehow!) B(n) and B(n+1). And the tie relates to the left adjoint of a morphism B(n)→B(n+1).

So the stew is thickening nicely, but it looks like we’ll have to adjust the seasonings quite a lot!

JB: Right, this proof will take real thought. I don’t know ahead of time how it will go. But I’m very optimistic.

Stone’s representation theorem says the category of boolean algebras and boolean algebra homomorphisms is contravariantly equivalent to the category of Stone spaces and continuous maps. Let’s call this equivalence

S: BoolAlgop → Stone

S is a nice letter because the Stone space associated to a boolean algebra A should really be thought of as the ‘spectrum’ of that algebra: it’s the space of boolean algebra homomorphisms

f:A → {⊤,⊥}

Our hyperdoctrine B gives a Boolean algebra B(n) for each n, and this gives us a Stone space S(B(n)). Maybe we can abbreviate this as Sn, as you were implicitly doing, and hope no symmetric groups become important in this game. But for now, at least, I want to keep our eyes on that functor S.

Why? Because our hyperdoctrine doesn’t just give us a bunch of Stone spaces: it gives us a bunch of maps between them! For each function

f: m → n

our hyperdoctrine gives us a boolean algebra homomorphism

B(f): B(m) → B(n).

Hitting this with the functor S, we get a continuous map going back the other way:

S(B(f)): S(B(n)) → S(B(m)).

And all this is functorial. That has to be very important somehow.

Next: somehow we want to use the Henkin trick to fatten up the Stone spaces S(B(n)) to sets of the form Vn for a fixed universe V. There are a lot of tantalizing clues for how. First, we can actually think about the Henkin trick and its use of “witnesses”. Second, we can note that the Henkin trick is related to existential quantifiers—which in hyperdoctrines are related to left adjoints in the category of posets to the boolean algebra homomorphisms

B(f): B(m) → B(n).

This raises a natural and interesting question. If you have a mere poset map between boolean algebras, what if anything does it do to their spectra? I should at least figure out the answer for the left adjoints we’re confronting.

So, there’s a lot to chew on, but it’s very tasty.

MW: Model theorists call these Stone spaces the spaces of complete n-types. We ran into them several times in our conversation on non-standard models of arithmetic (in posts 1, 2, 9, 18, and 25).

Let me noodle around with what you just said for a nice easy example, the theory LO of linear orderings. Actually, let’s start with something even easier: DLO, dense linear orderings without endpoints. This enjoys quantifier elimination: any formula is equivalent to one without quantifiers.

So, B(0) is just {⊤,⊥}. That makes sense: since DLO is complete, any sentence is provably true or provably false.

How about B(1)? Also {⊤,⊥}! What can we say about x? Provably true things like x=x, and provably false things like x≠x. That’s it!

Look at it this way: all countable DLO’s are isomorphic, and there’s an automorphism taking any element of a countable DLO to any other element. So all countable DLOs look alike, and for the elements of one, “none of these things is not like the other…”

For B(2) we finally have a bit of variety: B(2)={[x<y],[x=y],[y<x]}. Plus disjunctions like [x<y ∨ y<x]. And ⊥. What about the map B(f):B(1)→B(2) with our old friend f:{x}→{x,y}? Obviously ⊤ goes to ⊤ and ⊥ goes to ⊥.

Finally with B(3) things start to pick up a little. It contains the six “permutation situations” [x<y<z], [x<z<y], …, [z<y<x], plus seven more where some things are equal (like [x=y<z] or [x=y=z]), plus all the disjunctions, plus ⊥. If f now is the injection {x,y}→{x,y,z}, then B(f) sends an assertion about x and y to the disjunction of all the xyz situations consistent with it. For example

[x<y] ↦ [z<x<y ∨ z=x<y ∨ x<z<y ∨ … ∨ x<y<z]

Okay, complete n-types. (We’re concerned here with complete pure n-types, that is, no names added to the language.) These give you the full scoop on the n elements (x1,…,xn). So ignore the disjunctions. For DLO, we have only principal n-types: a single formula tells the whole story. I’ll write 〈φ〉 for the n-type generated by the boolean element [φ]. So for DLO,

| S(B(0)) = {〈⊤〉} |

| S(B(1)) = {〈⊤〉} |

| S(B(2)) = {〈x<y〉, 〈x=y〉, 〈y<x〉} |

| S(B(3)) = {〈x<y<z〉, 〈y<x<z〉,…, 〈x=y=z〉} |

In other words, we can forget about the disjunctions, and an n-type must be consistent. Take a hike, ⊥!

In general, if h:X→Y is a boolean algebra homomorphism, then S(h):S(Y)→S(X) is just inverse images: S(h)(p)=h−1(p). Here p, being an n-type, is a subset of Y. For example, let f:{x,y}→{x,y,z}. Above we saw that B(f):[x<y] ↦ [z<x<y ∨ … ∨ x<y<z]. All these disjuncts are sent to 〈x<y〉. (Or to be persnickety, the principle ideals generated by the disjuncts are sent there.)

That makes sense. The 3-type p is “full info” on the triple (x,y,z), and S(B(f))(p) extracts all the info we can glean about the pair (x,y). That’s a 2-type!

Hmm, couple of ways I could go from here. On the one hand, I don’t yet discern any existential quantifiers lurking in the background. Also, what do we want for our “universe” or “domain” V? None of the B(n)’s, n=0,1,2,3, seem to be co-operating!

Or I could repeat the exercise for a less simple theory, namely LO. Now B(1), and even B(0), have some real meat on their bones! Quantifiers stick around.

I don’t have such a clear understanding of the n-types of LO. Maybe if I finish reading Joe Rosenstein’s marvelous book…

Oh, one more thought. The contravariant S functor gives us S(f) going in the other direction from f. But we need two morphisms going the other way: the left and the right adjoints.

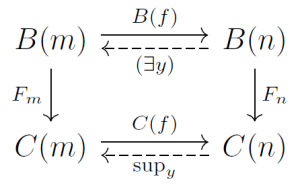

JB: Yes, I’ve been talking about the left adjoint since that relates to existential quantifiers, and those seem to be the key to “Henkinization”. My vague idea is this—I’ll just sketch a special case. If our hyperdoctrine B has some unary predicate P ∈ B(1) that gives “true” in B(0) when we existentially quantify it, Henkin wants to expand the Stone space S(B(1)) by throwing in an element x such that P(x) = ⊤. (Remember, elements of B(n) are precisely continuous boolean-valued functions on the Stone space S(B(n)).)

And here, when I said “existentially quantify it”, I meant take an element of B(1) and hit it with the left adjoint of the boolean algebra homomorphism

B(f): B(0) → B(1)

coming from the unique function

f: 0 → 1

Does this make sense?

If so, of course we need to do this sort of thing in a way that involves not only B(0) and B(1), but also the boolean algebras B(n) for higher n.

To make progress on this idea, it’s very good that you found a nice example of a hyperdoctrine, namely the theory of dense linear orders, and started working out B(n) for various low n. I think we should focus on this example for a while, and think about trying to “Henkinize” it, throwing new elements into the Stone spaces S(B(n)), until we get a set-based hyperdoctrine C, i.e. one for which every C(n) is the power set of Vn for some fixed set V. This will be a countable infinite set, right? It’s probably the underlying set of some Stone space. And it should be obtained in some systematic way from our original hyperdoctrine B.

You’ve nicely shown why B itself is not set-based.

MW: Sounds like a plan!

Prev TOC Next