We saw how Cantor introduced ordinals originally as “symbols”,

0, 1, 2,…; ∞, ∞+1, ∞+2,…; 2∞, 2∞+1,…; 3∞,…; 4∞,…

∞2, ∞2+1,…; 2∞2,…; 3∞2,…; ∞3,…; ∞4,…

∞∞,…; ∞∞∞…; ∞∞∞∞…

Later on he changed the notation, replacing ∞ with ω and switching the order of ordinal multiplication: ω2 instead of 2ω.

The sequence of ordinals goes on “forever”, so after

ω, ωω, ωωω, ωωωω…

we have an ordinal Cantor called ε0. But then we have ε0+1, ε02, ε0ε0… It never ends.

Cantor tried to place this intuition on a firmer basis, first with his two “principles of generation”:

- If α is any ordinal, then there is one immediately following it, α+1.

- If any definite succession of ordinals exists for which there is no largest, then there is one immediately following all of them, which is thought of as the limit of these ordinals.

But the second principle is still pretty vague. Cantor later decided his notion of order types was the way to go. If M is a simply (aka linearly) ordered set, then M is its order type, obtained by “abstracting” away the nature of its individual elements. In practice, this just means that if M1 and M2 are ordered sets and there is an order-preserving bijection between them, then M1=M2.

Cantor said that a simply ordered set M is well-ordered when

- M has a least element.

- For any subset M′⊆M, if there is an element y with M′<y (i.e., m<y for all m∈M′), then there is a least element greater than M′: an element x with M′<x, but with no y such that M′<y<x.

The connection between the second condition and the second principle of generation is clear. Cantor showed the equivalence of condition (2) to the simpler condition

2′. Every nonempty subset N⊆M has a least element.

We have transfinite induction on any well-ordered set M. Suppose P is a property of elements of M such that: if P(y) holds for all y<x, then P(x) holds. Then P holds for all of M. Proof: let N be the set of elements of M for which P doesn’t hold. N must be empty, for otherwise its least element contradicts the assumption about P.

Cantor now defined an ordinal to be the order type of a well-ordered set. 1 is the order type of any singleton, 2 the order type of any pair, etc. (0 is a special case; Cantor ignored it.) Also, ω is the order type of the natural numbers.

You obtain an order type from a “process of abstraction”, but Cantor never explained what he meant by this. As we’ve seen, Frege made fun of this. But his (and Russell’s) replacement (three is the class of all trios) doesn’t work either, because of Russell’s paradox.

Here is a key result (if we allow 0):

For any ordinal α, the set {β:β<α} is a well-ordered set with order type α.

This suggests the modern definition of ordinals, due to von Neumann. The order type of {0,1,2} is 3. The order type of {0,1,2,…} is ω. Why not define α to be the set of all preceding ordinals? So:

0 = ∅

1 = {0} = {∅}

2 = {0,1} = {∅, {∅}}

3 = {0,1,2} = {∅, {∅}, {∅, {∅}}}

⋮

and ω={0,1,2,…}. Also ω+1=ω∪{ω}. In general, for any ordinal α, its successor is α∪{α}.

The predecessors of an ordinal are exactly its elements: β<α iff β∈α. So the elements of an ordinal are simply ordered under ∈. In fact, well-ordered.

Each ordinal is also transitive: if γ∈β∈α, then γ∈α. von Neumann defined ordinals by these two properties:

Definition: An ordinal is a transitive set that is well-ordered under ∈.

We need transitivity, otherwise (for example) {5} would compete with {0} for the title of “1”.

This definition makes the development a bit slicker; I’ll use it from now on. It also solves the vexing abstraction question. If W is a well-ordered set, then it can be shown that W is order equivalent to exactly one von Neumann ordinal; that’s the order type of W.

I won’t go through a systematic development of the theory; right now let’s aim for some more intuition. (Later I’ll fill in some of the details.)

For Cantor, an ordinal α is countable when the set {β:β<α} is countable. But with the von Neumann definition, this set is α. All the ordinals mentioned above are countable. To take an easy example, consider ω2. The ordinals less than it are

| 0, | 1, | 2, | 3, | … |

| ω, | ω+1, | ω+2, | ω+3, | … |

| ω2, | ω2+1, | ω2+2, | ω2+3, | … |

| ω3, | ω3+1, | ω3+2, | ω3+3, | … |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

We can enumerate these using the same “short diagonal” method used to enumerate the rationals:

0, 1, ω, 2, ω+1, ω2, 3, ω+2, ω2+1, ω3,…

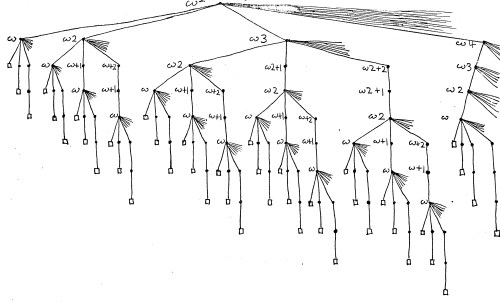

Of course this enumeration does not preserve the order. The ordinal ω2 can be pictured via an “ordinal tree”, like so:

Generalizing, if we have a sequence of countable ordinals α1<α2<…, then limn αn is countable. (Definition: limn αn is the least ordinal greater than all the αn’s.)

Proof: list all the ordinals less than α1 in the first row, all ordinals ≥α1 but <α2 in the second row, etc. Using the same short diagonal method, we have a listing of all ordinals less than limn αn.

The idea that the reals can be well-ordered is somewhat hard to stomach; it generated most of the initial skepticism about the axiom of choice. It seems impossible to picture a well-ordering of the reals. We can make this more precise.

Definition: say an ordinal α is realizable in ℝ if there is a subset A⊆ℝ whose order type, under the natural ordering of ℝ, is α. Examples:

- ω is realized by ℕ⊂ℝ.

- ω+1 is realized by {0, ½, ¾, 7⁄8,…}∪{1}.

- ω2 is realized by

{0, ½, ¾, 7⁄8,…}

∪{1, 1½, 1¾, 17⁄8,…}

∪{2, 2½, 2¾, 27⁄8,…}

⋮ - ω2+1 is realized by

{0, ½, ¾, 7⁄8,…}

∪{1, 1¼, 13⁄8, 17⁄16,…}

∪{1½, 15⁄8, 111⁄16,…}

∪{1¾,…}

∪{17⁄8,…}

⋮

∪{2}

Etc. Of course, you can realize each of these ordinals in ℝ in infinitely many ways. The basic trick: there is an order preserving bijection from ℝ onto the open unit interval. If you “use up” all of the space from 0 to ∞ with an ordinal α, just squeeze it down so it fits into the unit interval and you then have room on the right to add more elements. I think of “realizable in ℝ” as a precise version of “can be pictured”.

Here’s a theorem: An ordinal is realizable in ℝ iff it is countable. To prove this, we start with a lemma.

Lemma: If α is a countable ordinal, then there is a sequence γ0<γ1<… with limn γn =α.

Proof: Let β0,β1,… be an enumeration of {β:β<α}. Let γ0=β0, and inductively let γn+1 be the earliest βk with βk >γn. By “earliest”, I mean with the least subscript k. It is easy to check that the sequence of γ’s does the trick.

Theorem: An ordinal is realizable in ℝ iff it is countable.

Proof: First we show that all countable ordinals are realizable in ℝ. Let α be countable, and assume (transfinite inductively) that all ordinals less than α are realizable in ℝ. Let γ0<γ1<… be the sequence provided by the lemma. So each γn is realizable in ℝ. Using the “squeezing” trick, there is a subset Gn of the open interval (n,n+1) with order type γn under the natural order of ℝ. The order type of ⋃Gn is obviously greater than or equal to all the γn’s, and so is an ordinal ≥α that is realizable in ℝ. But it is also clear that if an ordinal is realizable in ℝ, then so are all ordinals less than it.

In the other direction, if α is realizable in ℝ, then let A be a subset of ℝ with order type α. So there is an order-preserving bijection f between {β:β<α} and A. Let β<α. Let rβ be a rational number strictly between f(β) and f(β+1). (If β+1=α, then let rβ be some rational number greater than f(β).) The map β↦rβ is a bijection between {β:β<α} and a subset of ℚ. Therefore α is countable.

David Madore has a cool applet that can “draw” many ordinals. John Baez wrote three breezy posts about countable ordinals.

Cantor denoted the set of all countable ordinals by Z(ℵ0).1 He proved that its cardinality is ℵ1, the next cardinality greater than ℵ0. On the one hand, if Z(ℵ0) were itself countable, then we could arrange its elements in a sequence α1<α2<…; as we’ve seen, limn αn would then be countable. But then limn αn would be a countable ordinal greater than all the ordinals in Z(ℵ0), the set of all countable ordinals!

For the other direction, here’s the basic idea. If M is an uncountable well-ordered set, then (using transfinite induction) we can map all of Z(ℵ0) 1–1 into M. We can’t run out of elements of M because M is uncountable. So the cardinality of Z(ℵ0) is less than or equal to the cardinality of any uncountable well-ordered set.

Now we appeal to the well-ordering theorem, a consequence of the axiom of choice: every set can be well-ordered. For Cantor, this was practically an article of faith.

[1] This isn’t quite correct. Actually, Cantor denoted the set of countably infinite ordinals by Z(ℵ0), and called it the second number class. But this turns out not to matter for what I say here.

0 doesn’t satisfy Cantor’s requirement (1). But otherwise that requirement is superfluous. We get better theorems by dropping it and allowing 0; for example, the key result that you cite after this is incorrect for finite ordinals without 0.

(Also, an editing error: The paragraph between this remark and the key result is a near replica of a paragraph from earlier, so you probably don’t want it anymore.)

Notice that this set is well-ordered, and using the von Neumann ordinals, Z(ℵ0) is itself an ordinal: ω1, the first uncountable ordinal. (This is true as long as we use the broad sense of ‘countable’ that includes finite sets as a special case; although the order type of Z(ℵ0) is ω1 either way.) Perhaps you’re planning to go there next.

(It’s disappointing that WordPress showed the subscripts in the edit box but didn’t post them. At least it did the italics.)

Thanks! I incorporated some of your suggestions into the post. I was able to fix the formatting of your comment.

I always use “countable” in the broader sense, and “countably infinite” for the stricter sense.

Cantor “did not dwell on the empty set”, as Kanamori puts it in his paper “The Empty Set, The Singleton, and the Ordered Pair”. For example, his version of the condition (2′) refers to “parts” of a set, implicitly nonempty.

I think that that’s a good way to use ‘countable’, but I was more concerned about what Cantor means by Z.

If Z(κ) is the set of all ordinals with cardinality κ, then assuming that κ is infinite, the order type of Z(κ) is the smallest ordinal with cardinality greater than κ. If instead Z(κ) is the set of all ordinals with cardinality κ or less, then Z(κ) not only has that order type but is that smallest ordinal. But this is using von Neumann ordinals, which Cantor didn’t have, so he may not have thought that this choice was important.

With finite κ, the difference is starker. Then the set of all ordinals with cardinality κ is a singleton, so its order type is always 1. But the set of all ordinals with cardinality κ or less is again the smallest ordinal with cardinality greater than κ, so this is clearly the better way to go. So Cantor would have used the better definition of Z if he’d thought about using it with finite ordinals … except that again once again it doesn’t work correctly without 0!

You’re right actually: Cantor used Z(ℵ0) to mean the set of countably infinite ordinals, what he called the second number class.

So far as I know, Cantor never used Z(𝔞) for any other cardinal 𝔞. He treats the finite cardinals in the first part of his capstone paper, “Contributions to the Founding of Transfinite Set Theory” (starting with 1) without using the Z notation. The result about Z(ℵ0) comes near the end of the second part.