Prev TOC Next

The Whirlpool Force: Early Thoughts

In the Astronomia nova, Kepler introduced the whirlpool force this way:

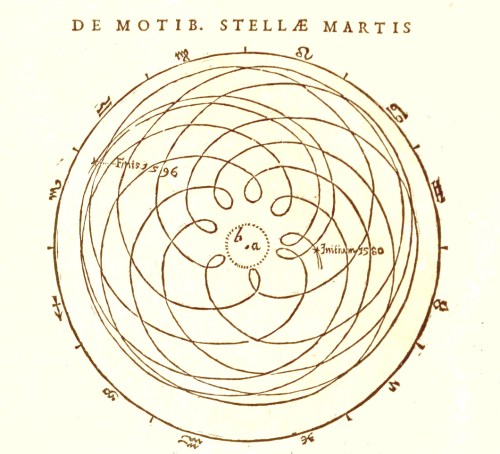

… since there are (of course) no solid orbs, as Brahe has demonstrated from the paths of comets, the body of the sun is the source of the power that drives all the planets around. Moreover, I have specified the manner [in which this occurs] as follows: that the sun, although it stays in one place, rotates as if on a lathe, and out of itself sends into the space of the world an immaterial species of its body, analogous to the immaterial species of its light. This species itself, as a consequence of the rotation of the solar body, also rotates like a very rapid whirlpool throughout the whole breadth of the world, and carries the bodies of the planets along with itself in a gyre, its grasp stronger or weaker according to the greater density or rarity it acquires through the law governing its diffusion.

Voelkel calls this the motive force hypothesis. As we’ve seen, Kepler devised it quite early, inspired by the steady decrease in planetary speeds with increasing orbital radii.

In the Mysterium cosmographicum, in a chapter titled “Why a planet moves uniformly about the center of the equant”, he adduced a new argument: the changing speed in a single orbit. The speed at perihelion is faster than at aphelion; in fact, the speed ratio is the inverse of the distance ratio:

vperi/vap = rap/rperi

We saw in post 4 that all three laws (the equant, the inverse distance, and the area law) give this relation.

So we have two similar phenomena. Jupiter (for example) moves slower than Mars, and Mars at aphelion moves slower than Mars at perihelion. The distance from the Sun seemed to be the common factor.

Kepler delighted at finding a physical cause to replace the equant. He was out of step with most astronomers of the time. True, they despised the equant. But Copernicus had replaced its non-uniform motion with the uniform motion of a small epicycle (often called an epicyclet). This they admired, while rejecting heliocentrism.

Kepler’s old teacher Maestlin discovered a geometrical demonstration for the near-equivalence of the Copernican epicyclet with Ptolemy’s equant; he communicated this to Kepler in a letter in 1595. (See Voelkel (p.19) or Evans (p.1013) for the proof.) The next year, in the Mysterium cosmographicum, Kepler wrote:

The path of the planet is eccentric, and it is slower when it is further out, and swifter when it is further in. For it was to explain this that Copernicus postulated epicycles, Ptolemy equants… Therefore at the middle part of the eccentric path … the planet will be slower, because it moves further away from the Sun and is moved by a weaker power; and in the remaining part it will be faster, because it is closer to the Sun and subject to a stronger power…

Nowadays we know that these two phenomena stem from different physics. Kepler’s second law reflects the conservation of angular momentum; it would hold with any central force. Kepler’s third law comes from the inverse square law for gravity plus the formula for centripetal force: F ∝ 1/r2 and F ∝ v2/r. For orbits with small eccentricities, we have approximately

| v ∝ 1/r |

Kepler’s 2nd |

| v ∝ 1/√r |

Kepler’s 3rd |

From the start, Kepler favored an inverse distance law for the whirlpool force. In a letter to Maestlin in 1595, he suggested a way to derive the orbital radii from the much more accurately known periods. (He needed the radii to test his polyhedral hypothesis.) He noted that two factors contributed to the longer periods of the more distant planets. First, they have to traverse a longer orbit. Second, they do so at a slower speed. Now, the motive force originates in the Sun and spreads out evenly over the orbits, so it should diminish in inverse proportion. Here is the passage, quoted in Voelkel (p.39). (Kepler uses ‘motion’ to mean motive force (proportional to speed), ‘orbs’ to mean orbits, and ‘circles’ to mean circumferences.)

There is, as I said, a moving spirit [motrix anima] in the Sun. If equal motion and the same strength came from the Sun into all orbs, one would still circulate more slowly than another on account of the inequality of the orbs. The periodic times would be as the circles. For quantity measures motion. However, circles [go] as the radius, namely as the distance. Thus from the certainly-known mean motions we could easily construct also the mean distances. But another cause enters which makes the more remote slower. Let us take the experience [experimentum] of light. For as both light and motion are connected in their origin so also [are they connected] in their actions, and perhaps light itself is the vehicle of motion. Therefore, in a small orb and also in a small circle near the Sun, there is as much light as there is in a large and more remote sphere. Therefore the light is thinner in the large, and denser and stronger in the narrow. And this strength is in inverse proportion to the circles, or the distances.

Note the last sentence. In the Mysterium cosmographicum Kepler repeated the argument:

Let us suppose, then, as is highly probable, that motion is dispensed by the Sun in the same proportion as light. Now the ratio in which light spreading out from a center is weakened is stated by the opticians. For the amount of light in a small circle is the same as the amount of light or of the solar rays in the great one. Hence, as it is more concentrated in the small circle, and more thinly spread in the great one, the measure of this thinning out must be sought in the actual ratio of the circles, both for light and for the moving power. Therefore in proportion as Venus is wider than Mercury, so Mercury’s motion is stronger, or swifter, or brisker, or more vigorous than that of Venus, or whatever word is chosen to express the fact. But in proportion as one orbit is wider than another, it also requires more time to go round it, although the force of the motion is equal in both cases. Hence it follows that one excess in the distance of a planet from the Sun acts twice over in increasing the period; and conversely, the increase in the period is double the difference in the distances.

Perhaps you already see two problems with this. First, the analogy with light indicates an inverse square dependence, not inverse linear. Second, neither of these are the right law. Let T be the period and r the orbital radius. An inverse linear dependence for the whirlpool force dictates that T is proportional to r2; an inverse square, to r3. But T is proportional to r3/2, as Kepler would eventually discover.

Kepler convinced himself that the inverse distance law fit the available data. Note the end of the passage above: “the increase in the period is double the difference in the distances”. For example (with made-up numbers): Say Planets 1 and 2 have T1=100, T2=400, and r1=1000. T2−T1=300, or 3 times T1. The increase in the radii, i.e., r2−r1, should then be 1.5 times r1, or 1500. So r2 should be 2500. Compare this with the correct result of assuming T proportional to r2: r2=2000. (Kepler carries out a similar computation with Mercury and Venus.)

Kepler applied this procedure to adjacent pairs of planets, using the Copernican periods to calculate the ratios of the distances. The results agreed (sort of1) with the Copernican ratios for the distances. Still, the procedure makes no sense. In the second edition of the Mysterium cosmographicum (twenty five years later) Kepler added this footnote:

Here the mistake begins… Now what I ought to have inferred … is that the ratio of the periods is the square of the ratio of the distances, not because I hold it to be true, for it is only the 3/2th power, as we shall hear, but because it was the legitimate conclusion from this line of argument. You see how at this point the arithmetic mean was taken, by halving the difference, when the geometrical mean should have been taken.

Next: inverse square or inverse linear? Voelkel remarks

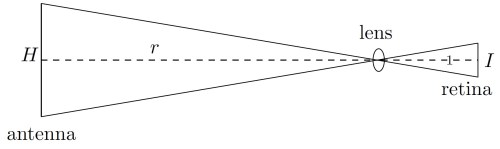

whereas light propagates spherically, Kepler confined his attention to the plane of the orbit… Only much later did he reconsider the spherical propagation of the motive virtue and address the problem of whether the strength ought, as light, to decrease as the square of the distance. [p.40]

And in a footnote Voelkel adds, “In his first thoughts about the propagation of motor virtue, he appears to have thought only about the plane of the orbit.”

Kepler’s Pars Optica (1604) clearly stated the inverse square law for light. By the time of the Astronomia nova, Kepler realized he had a problem. In his letter to Maestlin, he had said “perhaps light itself is the vehicle of motion”. In Chapter 33 of the Astronomia nova, he asserts

…although this light of the sun cannot be the moving power itself, I leave it to others to see whether light may perhaps be so constituted as to be, as it were, a kind of instrument or vehicle, of which the moving power makes use.

This seems gainsaid by the following: first, light is hindered by the opaque, and therefore if the moving power had light as a vehicle, darkness would result in the movable bodies being at rest; again, light spreads spherically in straight lines, while the moving power, though spreading in straight lines, does so circularly; that is, it is exerted in but one region of the world, from east to west, and not the opposite, not at the poles, and so on. But we shall be able to reply plausibly to these objections in the chapters immediately following.

In Chapter 36 he amplifies the second objection before resolving it:

This objection wearied me for a long time without offering any prospect of a solution.

It was demonstrated in Chapter 32 that the intension and remission of a planet’s motion [i.e., the time taken to traverse a given length] is in simple proportion to the distances. It appears, however, that the power emanating from the Sun should be intensified and remitted in the duplicate or triplicate ratio of the distances or lines of efflux. [I.e., as the square or cube of the distances.]

As this post is long enough, I’ll resume the story next time.

[1] But as Stephenson notes, the Copernican distances were not that accurate; Kepler’s third law would not have fit very well either.

Prev TOC Next

The Astronomia nova: “One Sustained Argument”

The Astronomia nova: “One Sustained Argument”