Prev TOC Next

MW: It’s been a minute! Well, almost 60,000 minutes.

We left off with a question: does a natural transformation from a syntactic hyperdoctrine to a semantic hyperdoctrine automatically “respect quantifiers”? We saw that this amounts to a Beck–Chevalley condition. We wondered if we had to add that condition to our definition of a model, or if it came for free.

Maybe you’ve had the experience of putting aside a crossword, half-completed, and coming back to it in a hour. Hey, of course the answer to 60 Across is “Turing Test”!

The same thing happened to me here. And the answer is: no free lunch.

Let me recap, just to get my brain back up to speed, and fix notation. B is a syntactic hyperdoctrine, C is a semantic hyperdoctrine, and F:B→C is a natural transformation.

For example: say B is the theory LO of linear orders, and C is an actual linear order. B(2) contains predicates like [x<y], C(2) contains binary relations on the domain of the linear order, and F2([x<y]) is the less-than relation on this domain.

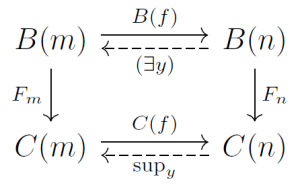

Here’s the key diagram:

Ignore the dashed arrows for just a second. Say f is an injection in FinSet, like f:{x}→{x,y}. Then B(f) and C(f) are the “throw in extra variables” morphisms we’ve talked about ad nauseum. This diagram is a commuting square in the category BoolAlg.

The dashed arrows are morphisms in a larger category we dubbed PoolAlg. This is a full subcategory of Poset, and BoolAlg is a so-called wide subcategory of it. Its objects are all boolean algebras, and its morphisms are all order-preserving maps, i.e., all the morphisms those objects have as denizens of Poset.

Within PoolAlg, the dashed arrows are left adjoints of the right arrows. Now does the diagram commute? In PoolAlg, that is. Beck–Chevalley says yes. We saw last time that we want this to be true. For example, the top left arrow takes [y<x] to [∃y(y<x)]. We want this predicate to map to the corresponding relation on an actual linear order. That’s what we mean by “respecting quantifiers”.

JB: This sounds right. Thanks for getting us started again!

As you might expect, I have a couple of nitpicks. While I feel sure there’s no free lunch here, I don’t think you have proved it. Maybe for some reason the Beck–Chevalley condition always holds in this situation! I feel sure it doesn’t, but I think that can only be shown with a counterexample: a defective model that doesn’t obey Beck–Chevalley.

It’s probably easy enough to find one. However, I don’t feel motivated to do it. We have bigger fish to fry. I’m happy to assume our models obey this Beck–Chevalley condition.

(Do we also need to assume they obey some sort of Frobenius condition?)

And here’s another even smaller nitpick: I don’t see the need for this category PoolAlg. I believe whenever you’re tempted to use it we can use our friend Poset. For example, the dashed arrows are left adjoints in Poset, and the square containing those dashed arrows commutes in Poset. Saying PoolAlg—restricting the set of objects in that way—isn’t giving us any leverage. It doesn’t seriously hurt, but I prefer to think about as few things as is necessary.

Maybe it’s time to finally try to state and prove a version of Gödel’s completeness theorem. Do you remember our best attempt at stating it so far? I think I can, just barely… though it’s somewhat shrouded by the mists of time.

MW: That’s right, to prove the “no free lunch” result we need a counter-example. That’s what came to me when I started thinking about this stuff again. A way to construct a whole slew of counter-examples.

And I think it’s worth going through, because it relates to Henkin’s proof of Gödel’s completeness theorem. The cat-logic proof will have to surmount the same obstacles. So here goes.

Say B is a theory, aka syntactic hyperdoctrine. Say C is a semantic hyperdoctrine, and F:B→C is one of those natural transformations that does respect quantifiers. Suppose the domain of C is V: C(n) is a set of n-ary relations on V. Now let W be a subset of V. Let D(n) be all the relations you get by restricting the relations in C(n) to W. And for any predicate φ∈B(n), let Gn(φ) be the restriction of Fn(φ) to W. Let be the image of B(n) under Gn. I claim that D is a hyperdoctrine, and G is a natural transformation from B to D. And very often, G will be disrespectful of quantifiers.

Using my LO example, let C have V=ℤ as its domain, and let W=ℕ. The predicate [y<x] gets sent to a less-than relation on ℤ by F2. This restricts to a less-than relation on ℕ. So G2([y<x]) is that relation.

Now let’s apply the left adjoints of the injection {x}→{x,y}. Up in B, we get the predicate [∃y(y<x)]. F1 sends this to the always-true relation in ℤ, which of course restricts to the always-true relation in ℕ. What about the left adjoints in C and D? The relation supy(y<x) is always true in ℤ, but is x≠0 in ℕ. So “go left, then down via G1’’ gets you to always-true in D, while “go down via G2, then left” gets you to x≠0.

Another example: let V=ℚ, W=ℤ, and for our predicate, use [x<z<y]. The left adjoint from {x,y}→{x,y,z} is [∃z(x<z<y)]. Taking one path brings us to the relation x<y in ℤ, while the other path leads to “follows, but not immediately”.

It’s clear now that one path leads to a “model” where ∃x means, “does there exist an x in a larger domain?”. The Henkin proof features a whole sequence of such enlargements. Thinking about that suggested this class of counter-examples to me.

I believe that restricting a semantic hyperdoctrine this way results in a hyperdoctrine. I haven’t checked all the details. But it’s a piece of cake when C(n) equals P(Vn) for all n. In that case, D(n) is just P(Wn)! This is what you wanted for semantic hyperdoctrines in the first place, as I recall.

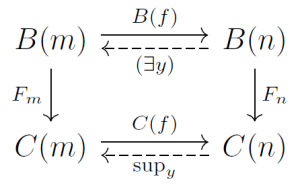

The other thing we need to check: that G is a natural transformation. The key

diagram:

Here, ↾m and ↾n are the restriction maps. It’s pretty obvious that the bottom square commutes. Since the top square does too, an easy diagram chase shows that “outer frame” square does.

Anyway, you wanted a refresher on the statement of the Gödel completeness theorem in our framework. Here goes. A syntactic hyperdoctrine B is consistent if B(0) is not the one-element boolean algebra {⊤=⊥}. The theorem states that every consistent syntactic hyperdoctrine has a model, which is a natural transformation to a semantic hyperdoctrine that respects quantifiers.

(And maybe also equality? Haven’t thought about that yet.)

We want to adapt the Henkin proof to this framework, is that right? I think I see, in a vague way, how to do that. But I don’t see how we’d be leveraging the framework—how the proof would be anything but a straighforward translation, not really using any of the neat category ideas.

JB: Okay, great. Thanks for all that.

Let’s try to clean things up a wee bit before we dive in. When you say “syntactic hyperdoctrine” I’d prefer to just say “hyperdoctrine”.

First, it seems plausible that any hyperdoctrine is consistent iff has a model. Second, part of the whole goal of working categorically is to break down the walls between syntax and semantics, to treat them both as entities of the same kind (in this case hyperdoctrines).

So, we should aim for a version of Gödel’s completeness theorem saying that a hyperdoctrine B is consistent iff it has a morphism F to a hyperdoctrine C of some particular “semantic” sort. You said B should be “syntactic”. That’s great as far as it goes, but here’s a place where we can generalize and do something new—so let’s boldly assume B is an arbitrary hyperdoctrine.

MW: Wait a minute! What do you mean by “morphism” here?

JB: A morphism of hyperdoctrines. Do you object? (That was a pun.)

MW: Who could object to a three layer cake?

In the bottom layer are boolean algebras, regarded as poset categories. The middle filling consists of categories whose objects are boolean algebras; a hyperdoctrine is a functor from FinSet to one of them. And now you propose to top it off with a category whose objects are hyperdoctrines. Copacetic!

Anyway, we never defined a morphism of hyperdoctrines. Do you mean a natural transformation respecting quantifiers?

JB: Well, perhaps not exactly that. We certainly want F to be a natural transformation respecting quantifiers, but we probably want it to be more than that, and we haven’t yet figured out exactly what. I expect that maybe F should be a natural transformation whose components obey the Beck—Chevalley and Frobenius conditions. That should make it respect quantifiers and equality. But we really need to think about this harder before we can be sure! So I said “morphism”, to leave the issue open.

We will probably resolve this issue as part of proving Gödel’s completeness theorem. It’s a time-honored trick in math: you make up the definitions while you’re proving a theorem, so your definitions make the theorem true.

Okay, where was I? I wanted to think about Gödel’s completeness theorem this way: it says a hyperdoctrine B is consistent iff it has some morphism F to a hyperdoctrine C of some “semantic” sort. And by “semantic” let’s mean the most traditional thing: we’ll demand that C be a hyperdoctrine where we pick a set V and let C(n) be the power set of Vn. That is semantic par excellence.

So how are we going to do this? Whatever trick people ordinarily use to prove Gödel’s completeness theorem—and you already mentioned the key word: “Henkin”—let’s try to adapt it to a general hyperdoctrine B. Maybe we can sort of pretend that B is defined “syntactically”, but try to use only its structure as a hyperdoctrine.

MW: Okay, this is the sort of thing I was hoping for!

I’m intrigued. The Henkin proof leans heavily on syntax. It begins by adding a bunch of new constants and axioms. How can we do this, while forswearing syntax?

JB: A question for the next installment….

Prev TOC Next