Nature of the Whirlpool Force

Kepler was unsure of the nature of the whirlpool force. Sometimes he compares it to light, sometimes to magnetism. Three successive marginal notes in Chapter 33 lay out the analogy with light: “The kinship of the solar motive power with light”; “Whether light is the vehicle of the motive power”; “The motive power is an immaterial species of the of the solar body”.

The Latin term species calls for a short discussion. Donahue (in his glossary) says:

This word, related to the verb “specio” (see, observe) has an extraordinarily wide range of meaning. Its root meaning is is “something presented to view”, but it can also mean “appearance”, “surface”, “form”, “semblance”, “mental image”, “sort”, “nature”, or “archetype” … I have therefore thrown up my hands, admitted defeat, and declined to translate it at all.

while Stephenson (p.68,footnote) writes:

“Image” is our rendering of Kepler’s species, which has for the most part been left untranslated in other accounts. As Kepler used it the word seems to mean the appearance or visible manifestation of the sun…

Gilbert’s De magnete furnished Kepler with another analogy, and a clue. Chapter 34 is titled “The body of the sun is magnetic, and rotates in its space.” A few quotes from it:

The magnet … has filaments (so to speak) or straight fibers (seat of the motor power) extended throughout its length. …it is credible that [the sun] … has circular fibers all set up in the same direction, which are indicated by the zodiac circle.

… It is therefore plausible, since the earth moves the moon through its species and is a magnetic body, while the sun moves the planets similarly through an emitted species, that the sun is likewise a magnetic body.

Kepler postulates filaments or fibers in the Sun as the source of the whirlpool force. These encircle the Sun along the circles of latitude. The Sun rotates, and the image of the moving fibers acts upon the planet to move it in the same direction.

Inverse Square vs. Inverse Linear

Taking a modern perspective, we have an inverse square law whenever we have a conservation law plus spherical symmetry. But with cylindrical symmetry (like the whirlpool force), we can have an inverse linear dependence.

A nice modern analogy: dipole radiation. Feynman discusses this in his Lectures, Chapter I-28:

The gradually discovered properties of electricity and magnetism … showed that these forces … fell off inversely as the square of the distance… As a consequence, for sufficiently great distances there is very little influence of one system of charges on another.

… Maxwell [to obtain a consistent system] … had to add another term to his equations. With this new term there came an amazing prediction, which was that a part of the electric and magnetic fields would fall off much more slowly with the distance than the inverse square, namely, inversely as the first power of the distance!

It seems a miracle that someone talking in Europe can, with mere electrical influences, be heard thousands of miles away in Los Angeles. How is it possible? It is because the fields do not vary as the inverse square, but only inversely as the first power of the distance.

He goes on to treat the dipole radiator. That is, an antenna. The key point: We have charges moving up and down the antenna. What matters is how that motion looks to a distant observer:

… all we have to do is project the motion on a plane at unit distance. Therefore we find the following rule: Imagine that we look at the moving charge … like a painter trying to paint a scene on a screen at a unit distance … We want to see what his picture would look like. So we see a dot, representing the charge, moving about in the picture. The acceleration of that dot is proportional to the electric field.

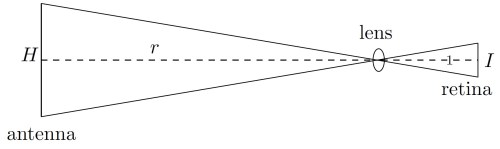

At root we have a simple matter of geometry. Substituting an eye for the painter, and the eye’s retina for the screen, we have the diagram below. We have a vertical antenna of height H at distance r from the eye’s lens. The image of the antenna on the retina has height I. The antenna has unit distance 1 from the lens. Thus:

From similar triangles, I/1=H/r. In other words, the length of the image is inversely proportional to the first power of the distance.

Note also that the symmetry is cylindrical and not spherical. If the line of sight is not perpendicular to the antenna, the image will be smaller, vanishing completely when the line of sight passes through the antenna.

Returning from Feynman’s Lectures to Kepler’s Astronomia nova, we can resolve the inverse-square problem. Instead of an antenna, we have the Sun’s circular fibers. Instead of the retina, we have the image (species) of those fibers moving the planet. The whirlpool force results from the sum total of those fiber images. Each image’s contribution diminishes inversely with distance, so the sum does too. For all the difference in the physics, the basic geometry remains the same for Feynman’s dipole and Kepler’s whirlpool.

Stephenson (p.75) puts it this way:

The composite motion was directed along a circle parallel to the sun’s equator (the resultant of the images of all the filaments) and it was therefore weakened—at any latitude—only as this circle expanded, in the simple proportion of distance.

This one sentence states the matter more clearly than Kepler does in Chapter 36. Nonetheless, the ingredients are all there, just scattered through the chapter.

One more thing: is the the whirlpool force is confined to the ecliptic? Some authors say that Kepler claimed this. Stephenson shows, with quotes, that this is not true. But something like it holds effectively. A planet above the solar pole would see the fibers moving in all directions, and the net effect would be complete cancellation. At intermediate latitudes, you get partial cancellation. Only at the ecliptic does the planet get the full effect. Figure 14 (p.75) of Stephenson illustrates this:

A final footnote. In 1645 Ismael Boulliau published his Astronomia philolaica. In it he noted, as Kepler had, that the whirlpool force should exhibit an inverse square dependence on distance. But he ignored Kepler’s solution to this problem. On the strength of this, the noted historian Thony Christie credits him with being The man who inverted and squared gravity. I am far less inclined to award him this accolade.