The Astronomia nova

The full title of the Astronomia nova is The New Astronomy, based upon causes, or celestial physics, treated by means of commentaries on the motions of the star Mars, from the observations of Tycho Brahe. This hits all the high spots: the treasure trove of Tycho’s observations, Kepler’s new physics, and the “battles with Mars”.

Historians have discovered that the Astronomia nova, although ostensibly a blow-by-blow account of Kepler’s process of discovery, in fact was (as Stephenson puts it) “one sustained argument”, written and rewritten carefully. So I will not initially deal with the topics in the same order.

Tycho’s Observations

The observational accuracy available to Ptolemy and Copernicus is generally taken to be about 10′, i.e., 10 arcminutes (Babb; Thoren, p.11), although errors of 40′ and more in his star catalog are frequent (Pedersen, p.252). Tycho’s observations rarely erred by more than 4′, and often were accurate to 1′ (Thoren, pp.11–12).

But just as crucial was Tycho’s systematic approach, following each planet throughout its orbit:

Previous astronomers had been clever, observing chiefly at critical moments, such as oppositions to the sun, when their observations gave clear answers to the questions they wanted to ask. Tycho’s less directed program proved its worth, naturally enough, when Kepler’s research reached the point where he had to ask questions that had not been thought of before.

—Stephenson (p.51)

We saw in post 4 that with a suitable choice of parameters, Ptolemy’s equant speed law and Kepler’s area law give the same speeds at perihelion and aphelion, and give nearly the same times for the planet’s arrivals at the quadrants. We will see that the data for the octants played a critical role in Kepler’s discoveries.

Actual Orbits

Thanks to the Planetary Hypotheses, we know that Ptolemy regarded his planetary models as physically real. By the time of Copernicus, however, most astronomers subscribed to the viewpoint expressed in Osiander’s (in)famous preface to De revolutionibus:

…it is the duty of an astronomer to compose the history of the celestial motions through careful and expert study. Then he must conceive and devise the causes of these motions or hypotheses about them. Since he cannot in any way attain to the true causes, he will adopt whatever suppositions enable the motions to be computed correctly from the principles of geometry for the future as well as for the past. The present author has performed both these duties excellently. For these hypotheses need not be true nor even probable. On the contrary, if they provide a calculus consistent with the observations, that alone is enough.

Cardinal Bellarmine enunciated this viewpoint in a letter to Paolo Foscarini, warning him not to advocate the Copernican hypothesis as reality:

To say that on the supposition that the Earth moves and the Sun stands still all the appearances are saved better than on the assumption of eccentrics and epicycles, is to say very well—there is no danger in that, and it is sufficient for the mathematician: but to wish to affirm that in reality the Sun stands still in the center of the world, and that the Earth is located in the third heaven and revolves with great velocity about the Sun, is a thing in which there is much danger.

Historians later called this attitude instrumentalism, in contrast with realism.1

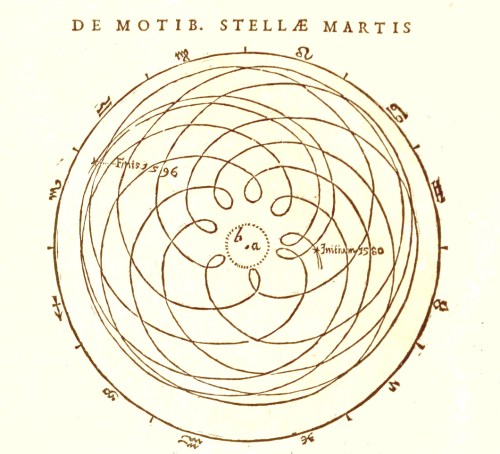

Kepler, like Copernicus (and Ptolemy and Peurbach) was a realist. The Astronomia nova includes, for the first time, a diagram of the actual orbit of Mars according to Ptolemy:

Donahue comments:

The figure on the facing page [see above] is a momentous diagram. Nothing like it had ever before been published. Astronomers had become so accustomed to thinking of celestial motions as compounded circular motions that it had apparently not occurred to anyone to consider the actual path traversed by a planet. Once the reality of the celestial spheres came into question, however, the actual path traversed came to be a matter of great interest.

— Donahue (p.35)

Expanding on the last sentence: the Planetary Hypotheses provides a physical mechanism for Ptolemy’s geometrical models, as we’ve seen. For a number of reasons (among them the discovery that comets would barrel right through the spheres) this mechanism seemed more and more dubious. The instrumentalists didn’t lose any sleep over this.

But for the realist Kepler, this “pretzel orbit” (as he termed it) constituted prima facie evidence againt the Ptolemaic and Tychonic systems2.

The Astronomia nova puts it this way:

But, with arguments of the greatest certainty, Tycho Brahe has demolished the solidity of the orbs, which hitherto was able to serve these moving souls [motrices animae, the beings that kept the orbs rotating], blind as they were, as walking sticks for finding their appointed road; and hence the planets complete their courses in the pure aether, just like birds in the air.

The realist approach has a couple of consequences. First, the longitude and latitude models must mesh properly to form a single consistent three-dimensional orbital geometry.

Second, if crystal spheres don’t guide the planets, what does?

[1] Centuries earlier, the Arabic polymath Averroös (Ibn Rushd, 1126–1198) complained, “The astronomy of our time offers no truth, but only agrees with the calculations and not with what exists.” [Wikipedia, longer quote in “The Search for a Plenum Universe” in Gingerich], p.140]

[2] The Tychonic system kept the Earth motionless but had the planets revolve about the Sun. It also suffered from ‘pretzelosis’.