The trichotomy of cardinals says that for any 𝔪 and 𝔫, exactly one of these holds: 𝔪<𝔫, 𝔪=𝔫, or 𝔪>𝔫. It’s equivalent to the conjunction of these two propositions, for any two cardinals 𝔪 and 𝔫:

- Antisymmetry:

- If 𝔪≤𝔫 and 𝔫≤𝔪, then 𝔪=𝔫.

- Comparability:

- Either 𝔪≤𝔫 or 𝔫≤𝔪.

Cantor showed the trichotomy of ordinals via transfinite induction. I outlined the proof at the end of post 5. If we assume that every set can be well-ordered, then trichotomy for cardinals follows immediately. For Cantor, this well-ordering assumption was a “law of thought”.

We can eliminate the notion of “cardinal number” from the statement of trichotomy. Write X≤Y if there is an injection from X to Y, and X≡Y if there is a bijection. Antisymmetry says that if X≤Y and Y≤X, then X≡Y. Comparability says that either X≤Y or Y≤X.

In 1915, Hartogs showed that trichotomy implies the well-ordering theorem and hence the axiom of choice. But antisymmetry is provable without using Choice. Once upon a time, people called this the Schröder-Bernstein theorem: in 1898 proofs appeared by Schröder and Bernstein (independently). Alas, Schröder’s proof suffered a fatal flaw. A proof by Dedekind turned up in his posthumous papers; he had also sent it to Cantor, who apparently didn’t notice it. Zermelo rediscovered Dedekind’s proof. So: Schröder-Bernstein? Cantor-Bernstein? Dedekind-Bernstein? Cantor-Dedekind-Berstein? Just Bernstein? Take your pick. I will call it the Equivalence Theorem.

Schröder’s “proof” is elegant, at least. Say f:X→Y and g:Y→X are the injections. Let X0=X and Y0=Y, and inductively define Yn+1=f(Xn) and Xn+1=g(Yn). Then

X0 ⊇ X1 ⊇ X2…

X0 ≡ X2 ≡ X4…

X1 ≡ X3 ≡ X5…

So ⋂nX2n=⋂nX2n+1. Schröder now asserts that the cardinality of ⋂nX2n is the same as the common cardinality of all the X2n, and likewise for ⋂nX2n+1. So X0≡X1≡Y0. But his assertion is false: we can have ⋂nX2n=⋂nX2n+1=∅, even with X and Y infinite. For example, let X=Y=ℕ, and f(n)=g(n)=n+1.

Dedekind’s proof uses an equivalent formulation. Since Y is equivalent to a subset of X, we might as well assume that Y actually is this subset. Then the injection f:X→Y is a map from X to itself. We have X ⊇ Y ⊇ f(X). We need to show X≡Y.

Let P=X∖Y and Q=Y∖f(X). Then

X=P ⊔ Q ⊔ f(P) ⊔ f(Q) ⊔ f(f(P)) ⊔ f(f(Q))…

Y= Q ⊔ f(P) ⊔ f(Q) ⊔ f(f(P)) ⊔ f(f(Q))…

Define h by h(x)=f(x) for x∈P ⊔ f(P) ⊔ f(f(P))…, and h(x)=x for x∈Q ⊔ f(Q) ⊔ f(f(Q))…. Verify that h is a bijection between X and Y. QED

An elegant proof, due to Julius König, often appears in textbooks. It’s longer than Dedekind’s proof; I will drag it out even more by offering some motivation.

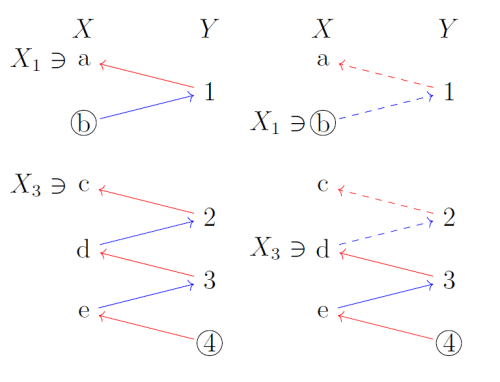

In the figure above, sets X and Y are indicated with the injections f:X→Y (blue) and g:Y→X (red). We want to construct a 1–1 pairing between all of X and Y out of these two partial pairing. Each edge, red or blue, is a possible pairing. So a node like b has two possible partners: 1 or 3. However, a node like a has only one possible partner, namely 2. Likewise, 1’s only possible partner is b.

That means we have to start by pairing off nodes without preimages: nodes x∈X for which g−1(x) doesn’t exist, and nodes y∈Y for which f−1(y) doesn’t exist. Let’s call this the first round of pairings.

Once we’ve paired off a2 and 1b, it then turns out that c and 3 each have only one possible choice (second round). And so on. In the figure, this is enough to complete the bijection. (Thickened edges indicate the pairings actually made.)

If you think about it, this procedure amounts to following the f and g edges backwards until you can’t go any further. Call this the backwards chain or just the chain. Suppose it starts with x=x1∈X and terminates in Y, say x1,y1,x2,y2…,xn,yn. (So g−1(x1)=y1, f−1(y1)=x2, etc., and f−1(yn) doesn’t exist.) In round 1, we must pair yn with xn=g(yn). In round 2, we must pair yn−1 with xn−1=g(yn−1). Eventually we must pair y1 with x1=g(y1). In other words, we pair x1 with y1=g−1(x1). We are forced to use g−1 for each pair xiyi.

On the other hand, if the chain starts and ends in X—say, x=x0,y1,x1, …,yn,xn, where g−1(xn) doesn’t exist—then we must pair xn with yn=f(xn), and then must pair xn−1 with yn−1=f(xn−1), eventually pairing x1 with y1=f(x1) and x0 with f(x0).

If the chain never terminates, then we have a choice. We can pair x with f(x) or with g−1(x). To make a definite rule, let’s always use g−1(x).

Summarizing, we have this definition of the bijection h:

h(x) = f(x) if the chain terminates in X

h(x) = g−1(x) if the chain doesn’t terminate

h(x) = g−1(x) if the chain terminates in Y

We know that g−1(x) exists in the last two cases, for if it didn’t, then the chain would terminate in X.

So we’ve partitioned X into three parts, X = X1 ⊔ X2 ⊔ X3:

X1={x∈X : the chain terminates in X}

X2={x∈X : the chain doesn’t terminate}

X3={x∈X : the chain terminates in Y}

and f is used on X1 while g−1 is used on X2 and X3. Now we have to show that h is a bijection.

First note that we get the chain for f(x) by prepending f(x) to the chain for x. The termination behavior is unaffected by this prepending, so f(Xi) is contained in Yi (i=1,2,3) where

Y1={y∈Y : the chain terminates in X}

Y2={y∈Y : the chain doesn’t terminate}

Y3={y∈Y : the chain terminates in Y}

Likewise, we get the chain for g(y) by prepending g(y) to the chain for y. So g(Yi) is contained in Xi (i=1,2,3). So both f and g “stay in their lanes”: a blue f-edge cannot cross from Xi to Yj with i≠j, and likewise for the red g-edges. So the same is true for f−1 and g−1, wherever they are defined.

Now, f is injective, and g−1 is injective on its domain (i.e., on g(Y)), and “the streams can’t cross”: if x∈X1 and x′∈X2⊔X3, then we can’t have h(x)=h(x′) because h(x)=f(x) is in Y1 and h(x′)=g−1(x′) is in Y2⊔Y3.

Note that f maps X1 onto Y1, because if f−1(y) doesn’t exist, then y belongs to Y3. Also g−1 maps X2⊔X3 onto Y2⊔Y3: If y∈Y2⊔Y3, then g(y) belongs to X2⊔X3 and g−1 maps it to y. QED

There is a version of the Equivalence Theorem for linearly ordered sets, due to Lindenbaum. Note that an order-preserving map f:X→Y of ordered sets is automatically injective: if x≠x′, then either x<x′ or x′<x, so either f(x)<f(x′) or f(x′)<f(x) and so f(x)≠f(x′).

We can have order-preserving injections f:X→Y and g:Y→X without any order-isomorphism between X and Y. Simple example: X is the closed interval [0,1] and Y is the open interval (0,1) (in either ℚ or ℝ). But we have the following:

Theorem (Lindenbaum): If f:X→Y is an order-preserving map onto an initial segment of Y, and g:Y→X is an order-preserving map onto a final segment of X, then there is an order-isomorphism between X and Y.

Proof: We will show that the h constructed above works. We already know it’s a bijection, so we just have to show that it’s order-preserving.

Since f and g are order-preserving, we are left with this to prove: if x∈X1 and x′∈X2 ⊔ X3, then x<x′ and f(x)<g−1(x′).

Observe that all elements of f(X) precede all elements of the complement Y∖f(X), since f maps onto an initial segment of Y. Likewise all elements of g(Y) follow all elements of X∖g(Y).

Now, if x belongs X∖g(Y), then the chain for x terminates in X, so x∈X1. For any x′∈X2⊔X3 the preimage g−1(x′) must exist, since its chain doesn’t terminate in X. So x′∈g(Y) and we have x<x′ in this special case. The figure above illustrates how to extend this to the general case of any x∈X1. It shows x=a∈X1 and x′=c∈X3. The terminal nodes in the chain, b and 4, are circled. Following the chain two steps gives us b∈X∖g(Y) and d∈X3. By the previous paragraph, b<d. But f and g are order-preserving, so g(f(b))<g(f(d)). That is, a<c.

The figure above illustrates how to extend this to the general case of any x∈X1. It shows x=a∈X1 and x′=c∈X3. The terminal nodes in the chain, b and 4, are circled. Following the chain two steps gives us b∈X∖g(Y) and d∈X3. By the previous paragraph, b<d. But f and g are order-preserving, so g(f(b))<g(f(d)). That is, a<c.

What if we had c∈X2 instead of X3? The argument is not affected. What if, traveling along the two chains in sync, the chain for x′ terminates before the chain for x? That would happen, for example, if 2 in the figure was a terminal node, without a preimage f−1(2). But then 1<2 because 1 belongs to f(X) and 2 belongs to Y∖f(X). So g(1)=a precedes g(2)=c.

Clearly this reasoning holds for any x∈X1 and x′∈X2⊔X3.

It remains to show that h(x)=f(x) precedes h(x′)=g−1(x′). Once again we can follow the two chains in sync until we hit a terminal node for one of them. Because f and g are order-preserving, we are reduced to proving two things:

- If x∈X∖g(Y) and x′∈X2⊔X3, then f(x)<g−1(x′).

- If y∈Y1 and y′∈Y∖f(X), then y<y′.

In both cases, we can “ascend the ladder”. That is, each bullet says that an f-edge has its Y-vertex above the Y-vertex of a g−1-edge. In the figure, the f-edges slope upwards and are blue, while the g−1-edges slope downward and are red. Applying f⚬g to the Y-vertex and g⚬f to the X-vertex moves us up “one rung”. So the general case, where x is any element of X1 and x′ is any element of X2⊔X3, follows from these two bullets.

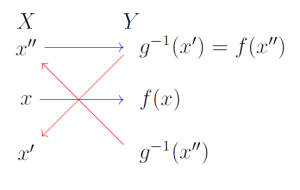

So let’s prove the first bullet. The argument (a proof by contradiction) is a bit tedious. This figure will make it easier to follow:

Suppose g−1(x′)<f(x). Since f maps X onto an initial segment of Y, this means that g−1(x′) also belongs to f(X). Say g−1(x′)=f(x″). Since f is order-preserving, and f(x″)<f(x), we have x″<x. Now, x′∈X2⊔X3 and x″ belongs to the x′-chain, so x″∈X2⊔X3 and is therefore in g(Y). But g maps Y onto a final segment of X, and x″<x, so x must also belong to g(Y). This contradicts the assumption that x∈X∖g(Y).

Suppose g−1(x′)<f(x). Since f maps X onto an initial segment of Y, this means that g−1(x′) also belongs to f(X). Say g−1(x′)=f(x″). Since f is order-preserving, and f(x″)<f(x), we have x″<x. Now, x′∈X2⊔X3 and x″ belongs to the x′-chain, so x″∈X2⊔X3 and is therefore in g(Y). But g maps Y onto a final segment of X, and x″<x, so x must also belong to g(Y). This contradicts the assumption that x∈X∖g(Y).

The second bullet is a breeze. As noted already, all elements of f(X) precede all elements of Y∖f(X). We’ve also seen that all elements of Y1 belong to f(X). QED

Rosenstein (pp.22–23) provides another proof, patterned after Dedekind’s proof of the Equivalence Theorem.

In recursive function theory, the Myhill Isomorphism Theorem is analogous to the Equivalence Theorem.