Mercury

Mercury refused to cooperate with Ptolemy’s basic paradigm. You might guess that the fault lies with Mercury’s larger eccentricity, but studies show that bad data bears most of the blame. Mercury hugs the Sun, only appearing near the horizon close to sunrise or sunset, hardly ideal observation conditions.

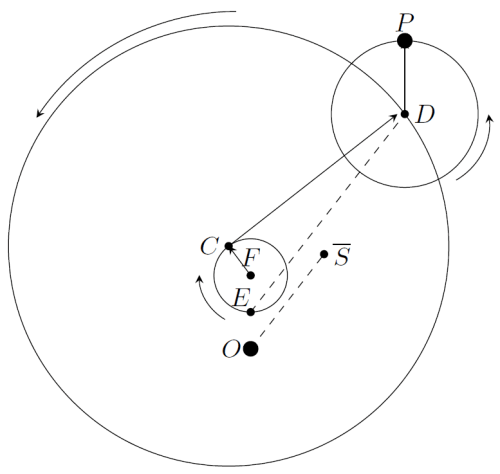

Ptolemy concluded from his data that the orbit of Mercury had two perigees. His model employs a trick used for the Moon: the center of the deferent rides on a small inner circle. Gingerich1 calls this little circle an epicyclet (and also a crank). Here is his model:

Unlike the Moon, but like the other planets, the epicycle and the deferent have the same rotation sense. This is because Mercury exhibits retrogressions. Like the Moon, the epicyclet has the opposite rotation sense from both.

C is the (moving) center of the deferent, E the equant, and F the center of the epicyclet. E bisects the line OF.2 The radius FC of the epicyclet is equal to FE and OE, so the epicyclet passes through E.

As with the other planets, the epicycle vector rotates uniformly. The equant-to-epicycle vector

rotates with uniform angular speed but varying length, while the deferent vector

rotates with varying angular speed but constant length—again like the other planets. The equant-to-epicycle direction ED is always parallel to the Earth-to-mean Sun direction OS, just like Venus (but not the outer planets).

The epicyclet vector rotates uniformly, with the opposite sense but same angular speed as the equant-to-epicycle vector

. The period of both is one year. (Technically, one tropical year.)

If we scrap everything stemming from the epicyclet, we are left essentially with the Venus model. That made good sense as a transformation of the Keplerian orbits. Given the much larger eccentricity of Mercury, it would have incurred greater inaccuracies, but it would have made for a decent approximation.

The epicyclet, like the Moon’s epicyclet, serves to bring the epicycle closer to Earth for part of the orbit. This makes it appear larger. In the Moon’s case, this reflected an actual perturbation of the Keplerian orbit (evection). Here the “perturbation” is not real, but an artifact of poor data.

Curiously, it turns out that the path of the point D—the “effective deferent”, so to speak—is very nearly elliptical. Despite this, Gingerich determined that the theory suffers from large errors, sometimes amounting to 12°. But the most severe errors would have been unobservable.

[1] Gingerich, “Mercury Theory from Antiquity to Kepler”, in The Eye of Heaven.

[2] This is not the bisection of eccentricity, where the (motionless) center C of the deferent bisects the line OC from the Earth to the equant.