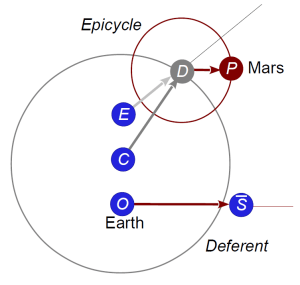

We’ve seen the basic plan for an outer planet in post 2:

The deferent represents the planet’s orbit about the Sun, the epicycle the Sun’s orbit about the Earth (in the geocentric frame). The rotating vector is always equal to

, and

is always equal to

.

As the Sun’s orbit is actually a Keplerian ellipse, we should use eccentric circles with equants for the epicycles. Ptolemy does not do this. In effect, he replaces the true Sun S with the mean Sun S. He retains the eccentricity and equant only for the deferent. As a result, the epicycle vector rotates uniformly, and would be equal to

, except for scaling (see post 2). Scaling makes the lengths different, but the vectors remain parallel. Really

functions more as a direction (or ray) than a vector. The outer planets boast significantly greater eccentricities than the Earth’s, so this scheme works out okay. Here are the eccentricities:

| Planet | Eccentricity |

|---|---|

| Mercury | 1/5 |

| Venus | 1/147 |

| Earth | 1/59 |

| Moon | 1/18 |

| Mars | 1/10 |

| Jupiter | 1/21 |

| Saturn | 1/18 |

The final model looks like this:

The vector rotates with uniform angular speed but varying length, while the vector

rotates with varying angular speed but constant length. As noted,

is always parallel to

.

Above I said that “in effect” Ptolemy did these things, but of course he didn’t look at it this way. He didn’t regard the epicycle as representing the Sun’s orbit; he had no reason to make the lengths of and

equal, any more than he had an explanation for why they are always parallel.

One more difference between my description and Ptolemy’s presentation: he deals with the angle between and the ray emanating from D in the direction

(shown in the figure). Modern practice uses a fixed direction towards some point on the celestial sphere—that’s the definition of longitude. Since

rotates uniformly, the two conventions are consistent.