Cantor’s Paradise

No one shall expel us from the Paradise that Cantor has created for us.

—Hilbert, “Über das Unendliche” [On the Infinite], in Mathematische Annalen 95 (1925)

I used to believe these myths about the history of set theory:

- Cantor began his investigations with the famous definition of “equinumerous” for sets as “having a 1-1 correspondence”.

- Next he proved that the rational numbers (and even the algebraic numbers) were countable, but (via the diagonal argument) that the reals are not. This led him to define “cardinality” for infinite sets. Later he came up with ordinal numbers.

- Cantor was devasted when he learned about Russell’s paradox, throwing his whole theory of sets into disarray. And just when it was finally gaining some acceptance!

I should have known that actual history is always more tangled.

Cantor embarked on his academic career by investigating trigonometric series. The details don’t matter to us; see Dauben’s biography for all the hair. He proved his first major result under the hypothesis that a certain set of exceptional points is finite. Cantor called this set P; P⊂ℝ. A year later (1872), he extended his result to the case where P′ is finite, where P′ is the set of limit points of P. (Definitions: x is a limit point of P if every neighborhood of x contains infinitely many points of P. P′ is called the derived set of P.)

Next Cantor defined the n-th derived set of P with the induction P(n) = (P(n−1))′, and showed that if the n-th derived set of P is finite, then the result still holds. One more extension: define P(∞) = ⋂nP(n). The result is still good if P(∞) is finite.

And it’s off to the races: next we define P(∞+1) = (P(∞))′, and P(∞+n) by the obvious induction. After that comes P(2∞) = ⋂nP(∞+n), then P(n∞), then P(∞2), …, P(∞∞), P(∞∞∞),…

We are witnessing the birth of ordinal numbers.

The 1872 paper bore the boring title “On extending a theorem from the theory of trigonometric series'”. Not only did it provide the first glimpses of ordinal numbers—the first section contained Cantor’s construction of the real numbers. That same year, Dedekind published his monograph with his “cut” construction of ℝ. He gave it the more dramatic title Continuity and Irrational Numbers. (Dedekind did this work much earlier, in 1858.)

In the 1872 paper, Cantor called the exponents ∞, ∞+1, etc. “symbols” and not “ordinals”. In 1883, in “Foundations of a General Theory of Sets”, he returned to the topic, with a new terminology and notation. Here we fine two “principles of generation”. The first principle is adding 1 to an ordinal. The second principle:

if any definite succession of defined [ordinal] numbers exists, for which there is no largest, then a new number is created by this second principle of generation which is thought of as the limit of those numbers, i.e., it is defined as the next number larger than all of them.

To celebrate the ordinals’ new status as real live numbers, Cantor switched from ∞ to ω.

Cantor actually wrote “realen Zahlen” instead of “ordinal numbers”; for “real numbers” in the sense of “elements of ℝ”, Cantor used “reelen Zahlen”.

OK, what about cardinal numbers? In 1874, he proved the uncountability of ℝ with a “nested shrinking interval” argument. (The diagonal argument didn’t appear until 1891.) Assume r1, r2, … is a sequence of all real numbers (without repetition). We will show there is a real number not in the sequence, giving us a contradiction. Let a1,b1 be the first two r’s such that a1<b1; let a2,b2 be the first two r’s such that a1<a2<b2<b1; etc. What if there are no such r’s? Since the reals are densely ordered, at least such a’s and b’s exist, and so we would have found a real not in the sequence. For example, if we’ve found a1<b1 but there is no ri between a1 and b1, then (a1+b1)/2 is a real not in the sequence. Note, since a2 and b2 are the first two r’s with this property, that any r’s earlier in the sequence must lie outside the interval from a1 to b1.

So we have a nested decreasing sequence of intervals (a1,b1)⊃(a2,b2)⊃… All the a’s and b’s are distinct, so their positions in the r-sequence grow without bounds. Therefore the intervals (an,bn) exclude ever longer initial segments of the r-sequence. Let a∞ = lim an, b∞ = lim bn. Obviously a∞≤b∞. If a∞<b∞, then any real number between a∞ and b∞ does not belong to the sequence of r’s. If a∞=b∞, then it’s easy to show that this common limit is not one of the r’s.

This proof doesn’t look much like the diagonal proof, does it? But Stillwell in his Roads to Infinity (§1.5) reveals connections. The diagonal argument is there, just hiding.

Cantor gave the 1874 paper the under-the-radar title, “On a property of the collection of all real algebraic numbers”. Kronecker was already growling at Cantor’s methods, and he was an editor of Crelle’s Journal. Dauben remarks:

The major result of the article, establishing the nondenumerability of R, was provocative enough by itself. But Cantor was very clever in his presentation, and his letters to Dedekind show he was being purposefully careful. The paper was really about the algebraic numbers, so Cantor said in print. The title indicated nothing more. The paper focused, seemingly, on this one result, and it introduced the proof of the nondenumerability of R only to enable an application of the paper’s title [namely, a new proof of the existence of transcendental numbers].

So now we have countable and uncountable sets. The stage is set for cardinal numbers.

The notions of cardinal and ordinal numbers evolved slowly and in parallel, from 1872 to Cantor’s last major paper in 1897. Initially 1–1 correspondences took the forefront. The algebraic numbers are countable, the reals aren’t—but ℵ0 and c made no appearance. In 1878, he offered this definition:

Two sets are said to be of the same power [Mächtigkeit] if a one-to-one correspondence between their respective elements is possible.

without defining “power” itself. An 1882 letter to Dedekind speaks of “[t]he concept of power which includes as a special case the concept of whole number…”

The 1883 paper “Foundations of a General Theory of Sets” put forth the two “principles of generation” mentioned above. The paper goes on to define the first number class as the collection of all finite ordinals, and the second number class as the collection of all countably infinite ordinals. Cantor showed that the power of the second number class is the next greater power after the power of the first number class. Or in his later notation, ℵ1.

This second principle of generation is a bit foggy. The next year Cantor came up with a new approach: ordinal numbers are the order-types of well-ordered sets. But he didn’t publish this until thirteen years later, in his last major paper: “Contributions to the Founding of Transfinite Set Theory” (appearing in two parts, 1895 and 1897). At that time, he also switched the order of ordinal multiplication: 2ω became ω2. And that’s when he christened the new creations ordinal numbers.

The “Contributions” defined a well-ordered set as a simply ordered set obeying two conditions: (1) It has a least element; (2) For any (nonempty) subset A, if there is an element greater than all elements of A, then there is a next greater element—that is, an element that is less than any other element greater than all of A. You can see the organic connection to his second principle of generation. Cantor showed that his definition is equivalent to the usual modern version, i.e., a simply ordered set where every (nonempty) subset has a least element.

The “Contributions” led off with a section titled “The Concept of Power or Cardinal Number”, in which we find this paragraph:

We will call by the name “power” or “cardinal number” of M the general concept which, by means of our active faculty of thought, arises from the set M when we make abstraction of the nature of its various elements m and of the order in which they are given.

We denote the result of this double act of abstraction, the cardinal number or power of M, by M̿.

Both this notation and the “double abstraction” idea had already appeared in an 1887 paper. Before that, in an unpublished paper in 1884, he wrote

The power of a set M is determined as the concept of that which is common to all sets equivalent to the set M and only these, and thus is also common to the set M itself. It is the representatio generalis…

Frege made fun of Cantor’s “act of abstraction”. What did it mean? It seemed purely psychological, not a sober mathematical definition. Both Frege and Russell preferred to define the cardinality of M as the set of all sets equivalent to M—a proposal with its own difficulties, as we will see.

The evolution of Cantor’s thought over twenty years is nicely illustrated by the 1–1 correspondence between ℝn and ℝ. He discovered this in 1877, and wrote to Dedekind, “Je le vois, mais je ne le crois pas.” (“I see it, but I don’t believe it.” Why these two German mathematicians corresponded in French, I don’t know.)

Cantor’s first proof interleaved the digits of decimal expansions. Taking n=2, (0.012…, 0.987…) would correspond to 0.091827…. Dedekind noticed a flaw: numbers with two representations, like 0.0999…=0.1000…. Let’s say we exclude the second form. But then (e.g.) 0.515050… corresponds to (0.555…, 0.100…), which uses the forbidden form.

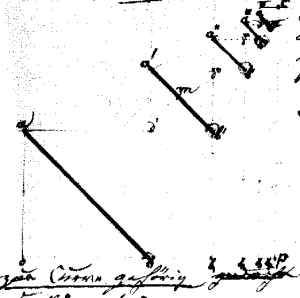

Cantor’s patch was clumsy and complicated. This diagram hints at his acrobatics:

Nowadays the workaround is easy: use the interleaving argument on the set B of infinite bitstrings. This gives a bijection between B×B and B, without hiccups. But we have an obvious map from B to the unit interval: use binary expansions. This map is 1–1 except for countably many points, which we can ignore since c+ℵ0 =c.

The “Contributions” gave this argument, expressing it with the equation

c·c = 2ℵ0·2ℵ0 = 2ℵ0+ℵ0 = 2ℵ0 = c

(except Cantor used 𝔬 instead of c for the cardinality of the continuum), adding

Thus the whole contents of my paper in Crelle’s Journal, vol. lxxxiv, 1878, are derived purely algebraically with these few strokes of the pen from the fundamental formulae of the calculation with cardinal numbers.

Another, highly significant example: the Continuum Hypothesis and the diagonal argument. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, Cantor occupied himself chiefly with point-sets (subsets of ℝ or ℝn). Recall that his first proof of the uncountability of ℝ used the order properties of ℝ in an essential way. In this context, the Continuum Hypothesis takes the form: any subset of ℝ is equivalent either to ℕ or to ℝ. No mention of cardinal numbers. Furthermore, Cantor had his hands (implicitly) on only two cardinals: ℵ0 and c.

The diagonal argument of 1891 immediately generalizes to any set. It shows that . So it gives us an unending succession of higher and higher cardinals. Nowadays we call these the beth numbers: ℵ0=ℶ0; 2ℶ0=ℶ1; 2ℶ1=ℶ2; 2ℶ2=ℶ3; etc.

As Cantor delved deeper into the ordinal numbers, he found he could apply them to the theory of cardinals. As noted above, the cardinality of the set of countable cardinals is ℵ1—the next cardinal greater than ℵ0. Before Cantor proved this, he didn’t know if “the next cardinal greater than ℵ0” meant anything—maybe it’s like asking for the next real number greater than 0! The proof generalized: if M is a well-ordered set, and M′ is the set of all ordinals of cardinality M̿, then is the next cardinal greater than M̿. Using this instead of the power set construction, we have the alephs: ℵ0 < ℵ1 < ℵ2 etc., with no cardinals in between.

The ordinals can be used as subscripts, extending the sequence of alephs: ℵω=∑nℵn, ℵω+1 is the next cardinal after ℵω, ℵω2=∑nℵω+n, etc.etc. (Likewise for the beths.)

Now, if M is any set, is its cardinality necessarily an aleph? Cantor’s theory of well-orderings furnished him with transfinite induction; with this, you can show that the answer is “yes” for any well-ordered (or well-orderable) set. Conversely, if M̿ is an aleph, then M is well-orderable.

Cantor firmly believed that every set can be well-ordered, and even asserted this (without proof) in one of his papers. This flowed (or so it seemed) from his “principles of generation”. Just keep picking elements from M to assign to ordinals. The principles insure you’ll never run out of ordinals. If you’ve assigned an mα for every α<β, either M is exhausted (in which case M is order-equivalent to the well-ordered set of all ordinals less than β), or if not, then pick an unused element of M to assign to β.

Needless to say, this is not a satifactory argument. In the closing years of the 19th century, Cantor strove without success to settle four open questions:

- Can every set be well-ordered? Equivalently, is every cardinal number an aleph?

- If we have injections from M into N and from N into M, does it follow that M and N are equivalent? In other words, if M̿≤N̿ and M̿≥N̿, do we have M̿=N̿? A “yes” follows from (1).

- Are the cardinal numbers simply ordered? The alephs are well-ordered, so (1) implies “yes”. A “yes” also follows from (2) plus the comparibility of any two cardinals, i.e., either 𝔪≤𝔫 or 𝔪≥𝔫 for any 𝔪 and 𝔫.

- The Continuum Hypothesis: 2ℵ0 = ℵ1.

Curiously, Cantor never wrote the CH down in the form (4). It immediately suggests the Generalized Continuum Hypothesis (GCH): 2ℵα = ℵα+1. for all ordinals α. The first to conjecture this, and write it this way, was Philip Jourdain in 1905. (Jordain also translated the “Contributions” into English.) From the GCH we conclude that ℵα=ℶα for all α.

This is very interesting. I think some details are being skipped over, though. For instance in the “nested shrinking interval” proof, if I pretend I don’t yet know anything like the result, at every step it’s nontrivial that any ri exist to continue the sequences of ai and bi, even if I assume you meant to say initially that every real is supposed to be one of the ri.

(I don’t mean this needed step is necessarily difficult, only that it’s not so trivial that it’s ok to leave it out. Note that I can’t just use the infinite number of reals to do this, since maybe asking for the “next ones that satisfy these inequalities” at some step, manages to skip over infinitely many reals.)

Okay, I edited the post to address your issue.

Unless I’m missing something, it doesn’t address my issue. The problem is with “after them” in the phrase “the first two r’s after them”. Yes, there is a real exactly between a1 and b1, but what if it occurred before b1 in the sequence of ri’s? What if all reals in that interval (a1, b1) had already occurred before b1 (and indeed before a1), preventing their use in place of b1?

I think it might fix things if you would replace “after them” with “other than them”.

Ah yes, I see your point. Thank you. Fixed.